Quaint startups become the next big thing.

From airbeds to circuit boards—how quaint ideas and tiny markets turn into the biggest businesses.

Welcome to Multitudes and greetings to the 42 of you who have joined since my previous post.

Essay up top and my favorite links of the week down below.

- Weisser

Some startups can tell you about the exciting future they will create from day one. These companies often get attention because they excite people about what's to come—or cause them to worry about what could go wrong. Yet this kind of startup is exceedingly rare. Most successful startups do not start out seeming like they will accomplish much at all. That is because they are quaint.

Quaint startups begin in such a humble and unassuming way that it is hard to predict they will amount to much. But imagining how they could become important in the future is essential if you want to be ahead of the curve. When successful, quaint startups seem to come from out of nowhere and capture or create entire markets.

I spend much of my time looking for quaint startups that could become the next big thing. If you are an investor or an ambitious person looking to join or start a company that could become successful, you should learn how to spot them too. The way to do that is by learning how quaint startups turn into huge startups.

Some concepts to pay attention to:

Deceptively Small Markets

Larger Adjacent Markets

Watching the Hobbyists

Timing and Inflections

Compounding and Patience

Deceptively Small Markets

We couldn't wrap our heads around air mattresses on the living room floors as the next hotel room and did not chase the deal.

We made the classic mistake that all investors make. We focused too much on what they were doing at the time and not enough on what they could do, would do, and did do.

- Fred Wilson reflecting on the decision to pass on investing in Airbnb

One of the biggest mistakes an investor can make is to assume a quaint startup's addressable market will not change in size. These investors look at a small market and fail to imagine what might happen if it were to grow.

Before Airbnb, the number of people paying to stay in a stranger's home for a night was effectively zero. The market size was the sticking point for many investors who passed on investing in the company. Fourteen years since its launch, over one billion guests have stayed at an Airbnb. That's often how quaint startups become hugely successful: they exponentially expand small markets.

To counteract this common bias about small markets, ask yourself what would be needed for a market to expand. Convenience, cost, and quality of experience are three of the most common variables that could help answer the question. Often they all come into play. For instance, Airbnb is slightly less convenient than a hotel. But it's usually a much better value and experience for guests—especially if more than two people are looking for a place to stay or for accommodation outside of a major city (Airbnb listings in a rural area are often far superior to budget motels).

Larger Adjacent Markets

The perfect target market for a startup is a small group of particular people concentrated together and served by few or no competitors.

- Peter Thiel, Zero to One

Quaint startups can succeed by saturating a small market before moving into larger adjacent ones. If the transition to a bigger market works out, it can cause a quaint startup to turn into one of the most important companies in the world.

Consider Apple's first computer. It was not a device for the uninitiated. It barely looked like what we'd think of a computer in modern terms. It was just a circuit board—no elegant case to enclose it or screen or keyboard included.

According to Steve Wozniak, he and Steve Jobs had planned to sell a bare circuit board with no components included. He thought they might be able to sell 50 of them to the hardware hobbyists they knew in Menlo Park—but it would not be easy. Instead of selling a bare circuit board that would require work for the purchaser to assemble, a personal computer retailer named Paul Terrell convinced the duo that customers wanted a prebuilt computer. Terrell offered to buy 50 immediately if they made them.

His experience selling the first Apple computer caused Steve Jobs to realize how a much larger group of people would be interested in a personal computer if it were ready to be used immediately upon purchase. That insight led to the Apple II, which included a sleek case that housed the internal hardware. It was a massive success and sold nearly five million units.

At first, [the computer] was a hobbyist tool. The Apple II was successful because we saw that for every hardware hobbyist that wanted to put a hardware kit together, thousands of software hobbyists didn't know how to do that and didn't have soldering irons but wanted to mess with software. So we sold the first ready-to-go personal computer.

- Steve Jobs, interview with Walt Mossberg (2003)

Few quaint startups discover a larger adjacent market and win it as Apple did with the Apple II. But that wasn't the last time Apple accomplished the feat—nor the most impressive. Their most significant move to a larger adjacent market would come two decades later with the launch of the iPod in 2001. Their new music player and the iTunes store would cause the company to become one of the most important in the world—moving beyond dominating personal computers and into the broader technology and media industries.

Follow the Hobbyists

What the smartest people do on the weekend is what everyone else will do during the week in ten years

- Chris Dixon, blog post (2013)

Inspiration for the Apple I came from Steve Wozniak's experience attending the first meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club. The club was the most important hobbyist group in the history of personal computing. Considering Apple's impact, Homebrew Computer Club might be the most impactful hobbyist group in the history of the world. Anyone interested in computers in the Bay Area would gather at the meetups to learn from each other and tinker with new ideas. These types of hobbyist communities are the type of environment from which monumental creations can emerge.

Nowadays, hobbyists don't necessarily need to congregate in physical spaces to benefit from each other's presence to create great things. Internet platforms have removed the geographic constraints for gathering and now bring together people who are thousands of miles apart.

Cryptocurrency came to prominence through small groups of online hobbyists gathering on forums. While difficult to imagine now, the idea for bitcoin—one of the most exciting developments of the 21st century—started as a single forum post.

The fact that Satoshi announced bitcoin on a forum instead of through coverage on a tech news site matters in the same way that it was critical for the Apple I to launch at the Homebrew Computer Club instead of in the New York Times. Hobbyists understand and embrace ideas before the general public does.

But not always. The risk with hobbyists is that they can be out of touch with the needs of a broader audience. For instance, if Apple continued to build with the Homebrew Computer Club members in mind, they'd never have gone on to create the iPod or iPhone. If those building web3 don't balance the maximalist ideals held by many early crypto hobbyists with pragmatic compromises, we'll likely never see it reach a wider audience. If Drew Houston, the creator of Dropbox, had listened to Linux hobbyists, he wouldn't have built a successful product that hundreds of millions use.

Even though they will sometimes get it wrong, it's worthwhile to pay attention to what other intelligent people are gravitating toward—regardless of how quaint or implausible. It is often where you will discover the next big thing.

Timing and Inflections

Quaint startups do not get created in isolation; the world around them is changing in ways that can help or hurt their chances of success. These changes are why one of the most crucial questions an investor must answer about a company is, "Why now?" Understanding what relevant inflections are underway can tell you if a quaint startup might become a big deal.

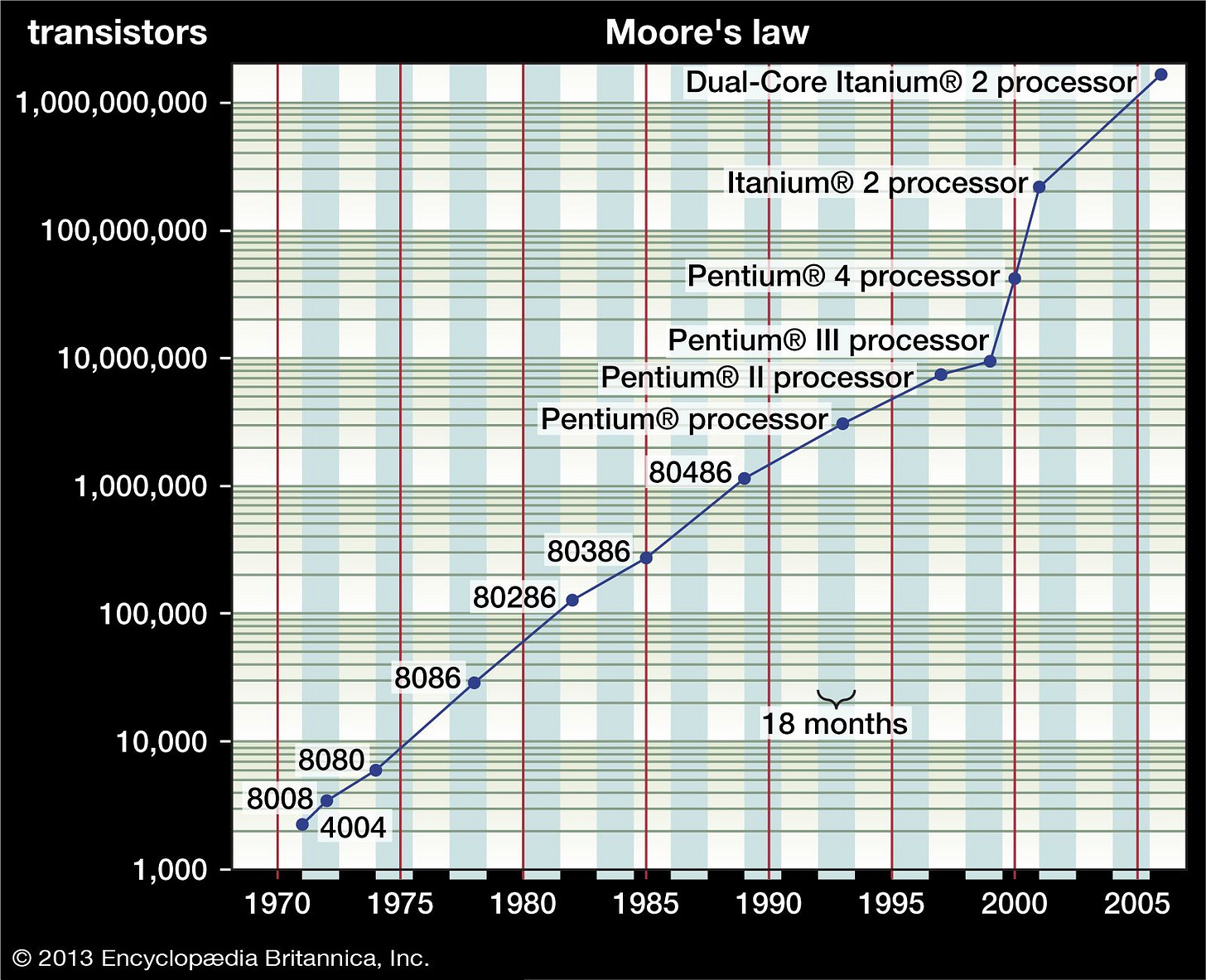

Microsoft started out making software for a market of a few thousand owners of an early personal computer called the Altair 8800. That is a small market if it doesn't grow. But it grew faster than anyone expected, and Microsoft's timing was impeccable. In the mid-1970s, the power of computer hardware was compounding, and the costs were plummeting. It was one of the most critical inflections in the history of technology, and Microsoft was well-positioned to be the software provider for that first wave of affordable computers.

Timing also played to Apple's advantage with the iPod. They launched it at precisely the right moment. Right before launch, an important milestone had occurred: for the first time, over 50% of US households had a personal computer. Computer access mattered because iPod users needed one to manage and upload their song libraries to their music players. In a bold move, Jobs reallocated the $75M computer advertising budget to market the iPod because he believed it would also cause them to sell more computers. He was right—Mac sales took off. The move also solidified iPod as the dominant mp3 player.

Compounding and Patience

Quaint things can take time to become big things. For example, the first Alcoholics Anonymous group started with just three people in 1935. After four years, the first three groups had helped 100 members reach sobriety. While I'm sure that achievement felt fulfilling for everyone involved, few would have guessed what was to come.

In the following eight decades, Alcoholics Anonymous would grow from three groups in the US to over 123,000 groups in 180 countries. On average, nearly four groups have been started every day since AA's founding. Four new groups every day for 85 years! That stat is all the more remarkable, considering how the first four years of AA only saw three groups created.

People have a hard time imagining just how big something can get when it starts very small. The starting point is so unremarkable that, even if there is growth, it is so gradual that it is often not noticed. Years later, the thing that was once small is suddenly big and growing fast. Always remember the impact of compounding on quaint initiatives (we often forget).

Quaintness and importance

Quaint startups that experience incredible success can often attribute this to more than one variable—for instance, building into an inflection point while expanding a small market. But all quaint startups have one thing in common: the earnest belief of the founders that what they're creating matters—even if just to a small group of people. Without that belief, nothing quaint can ever have the potential to become significant.

Some builders might see other young companies and projects directly addressing laudable goals like life extension or clean energy and worry that there's something less dignified in starting quaint. That brings me to one last piece of advice I'd like to impart to other builders: don't be embarrassed to create something that appears quaint if you feel it is worthwhile.

We should not exclusively pursue the obvious significant challenges of our times—many opportunities to build something important are apparent only in hindsight. There's also no telling what direction you and the project might take—something small today might change the world if given sufficient time and attention to develop.

If people stopped pursuing quaint things, we'd have far fewer big things that lead to a better future. Let's hope that never happens.

—

Thank you to Nathan Baschez, Jonathan Hillis, and Vikram Rajagopalan for reading and offering feedback on this essay.

—

I'm Julian. I co-founded On Deck and vote for the future by investing in Other founders. I love startlingly ambitious startups and quaint ones too.

Notable Links

Some exciting ideas, products, and news from companies I’m fortunate to work with.

Arkive acquires first issues of the Homebrew Computer Club newsletter

Arkive is building a decentralized Smithsonian museum and their latest acquisition is highly relevant to today’s essay.

XMTP launches direct messaging on Lens

XMTP is a secure and decentralized messaging protocol. This week they announced they’ve brought end-to-end encrypted direct messaging to Lens which is a decentralized social graph. If this sounds a bit nerdy an unneeded remember that most have felt that way one time or another past technological developments before they reached maturity. It feels especially timely given what’s happening at Twitter.

Roots (pay rent, earn equity) launches with 800 homes in Las Vegas

Interest rates have skyrocketed making homeownership even more of a daunting proposition than ever before. But people hate paying rent because it doesn’t enable them to build wealth through being a homeowner. That’s why it’s thrilling to see Roots launch with over 800 homes to choose from in Las Vegas. People who join Roots build equity alongside their monthly rental payment. Unlike buying a home the traditional way there’s no downpayment or long-term commitment. It’s a radical idea and I think it will replace renting as we know it (>1/3 of Americans currently rent).

”How I got 50 high-profile angel investors to join our seed round”

Niels is the founder of Mentava which helps kids learn to read fluently at 2-3 years old (among other skills). He is also did an exceptional job pulling in early supporters for his seed round. This post is one of my most useful resources for how to bring on excellent angel investors that I’ve come across. I’ll be sharing it constantly with founders who are preparing to fundraise.

My Philosophy of Product Building

Nathan’s latest piece for Every (which is having a 40% sale on a yearly subscription) is about his 0→1 approach on product. Nathan built an code editor that was acquired by General Assembly, the first version of Product Hunt, was the first employee at Substack, and recently launched the best word processing tool around—Lex (which I used to write this essay).